Why You Should Care About Greenwashing

If you’ve never given much thought to “greenwashing,” now would be a good time to start.

Motivated by growing environmental concerns, many consumers are making sustainability a significant factor in their buying decisions, and companies have responded by adding environmental claims to their marketing messages and product packaging.

As companies have increased their use of environmental claims, allegations of greenwashing have also increased. An October 2023 report by RepRisk found that over the previous year, 1,850 companies were linked to an incident of misleading communication, many of which were tied to greenwashing. In the United States, environment-related lawsuits by state attorneys general and private plaintiffs are multiplying, many of which have involved deceptive claims about recycling made on product packaging.

Governmental authorities are placing increased scrutiny on environmental claims, and several have adopted laws and regulations specifically dealing with such claims.

Under these circumstances, it’s vital that business leaders understand the complex and still-evolving legal and regulatory maze relating to environmental marketing claims.

Understanding Greenwashing

“Greenwashing” refers to making false, misleading, or unsubstantiated claims about the environmental impacts or benefits of a product or company to make it look more environmentally friendly than it actually is.

Greenwashing can occur in several ways. For example, the use of generic, but unsupported labels such as “green” or “eco-friendly” are usually viewed as a form of greenwashing. | See sidebar, "The Many Shades of Greenwashing"

Business leaders can be tempted to make questionable environmental claims because they recognize the value of having their company perceived to be on the right side of environmental issues.

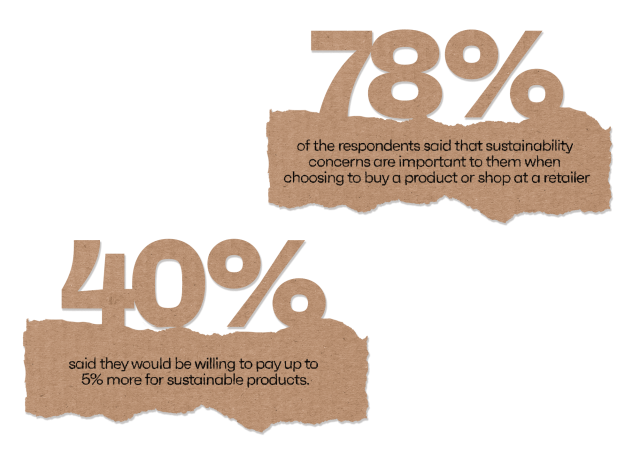

Numerous surveys have shown that many consumers consider sustainability when they make buying decisions. For example, in a 2024 survey of U.S. consumers by Blue Yonder, 78% of the respondents said that sustainability concerns are important to them when choosing to buy a product or shop at a retailer, and 40% said they would be willing to pay up to 5% more for sustainable products.

A 2023 study by McKinsey & Company and NielsenIQ found that environmental claims are correlated with greater sales growth. The researchers analyzed five years of U.S. sales data covering 600,000 individual product SKUs across 32 food, beverage, personal care, and household categories.

The analysis revealed that products making Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)-related claims averaged 28% cumulative growth over the five-year study period versus 20% cumulative growth for products that made no such claims.

The potential benefits of using environmental marketing claims are significant, but the risks of making misleading claims are also substantial. The greatest long-term risk is the loss of customer trust. When a company is accused of greenwashing, its reputation can be severely damaged, and it can take a long time to repair that damage.

In addition to reputational risk, false or misleading claims can also carry significant financial risk in the form of the costs and penalties or monetary damages resulting from regulatory enforcement actions or private litigation. | See sidebar, "The Three Faces of Greenwashing Risks"

Foundations of Green Marketing Regulation

This article discusses certain U.S. federal and state laws, regulations, judicial decisions, and certain Directives of the European Union. The content of this article is for general educational purposes only. It does not constitute, nor should it be construed as, legal advice. If you or your company has questions regarding the legality of an environmental claim or the applicability or interpretation of any law, regulation, or court decision, you should seek the advice of a qualified attorney.

Historically, the regulation of environmental marketing claims has been based on laws prohibiting deceptive business practices and/or false advertising.

In the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is the federal agency primarily responsible for policing the use of environmental marketing claims. The FTC’s authority is based on Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which provides in part that, “... unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce, are hereby declared unlawful.”

In addition, all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have consumer protection laws that prohibit deceptive business practices and/or false advertising. These laws have been frequently used to challenge deceptive environmental claims.

Most European nations had laws banning deceptive business practices before the formation of the European Union, but in 2005 the EU adopted Directive 2005/29/EC, which specifically prohibits unfair or misleading commercial practices. This Directive has been used to challenge deceptive environmental claims.

The FTC Green Guides

The FTC first issued Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims (the Green Guides or Guides) in 1992 in response to numerous requests for regulations or guidelines dealing specifically with environmental marketing claims.

The Green Guides are designed to help marketers avoid making deceptive environmental claims that violate the Federal Trade Commission Act. They are not legally binding regulations, but the FTC can take enforcement action if a company makes an environmental claim that is inconsistent with the Guides.

The Guides include four general principles that apply to all environmental marketing claims and specific guidelines for 14 common types of claims.

One of the key principles spelled out in the Green Guides is that environmental claims must be substantiated. Section 260.2 of the Guides provides in part:

"Marketers must ensure that all reasonable interpretations of their claims are truthful, not misleading, and supported by a reasonable basis before they make the claim ... In the context of environmental marketing claims, a reasonable basis often requires competent and reliable scientific evidence ... Such evidence should be sufficient in quality and quantity based on standards generally accepted in the relevant scientific fields, when considered in light of the entire body of relevant and reliable scientific evidence, to substantiate that each of the marketing claims is true."

The FTC’s Green Guides contain two provisions directly related to recycling. Section 260.12 addresses recyclable claims, and Section 260.13 deals with recycled content claims.

Recyclability

Section 260.12 states that it is deceptive to misrepresent that a product or package is recyclable. It also states that a product or package should not be marketed as recyclable unless it can be collected, separated, or otherwise recovered from the waste stream through an established recycling program for use in producing another item.

Section 260.12 also provides that marketers must clearly qualify claims to the extent necessary to avoid deception about the availability of recycling programs and collection sites. In order to make an unqualified claim, recycling facilities must be available to a “substantial majority” (60%) of consumers where the item is sold. Otherwise, the claim must be appropriately qualified.

Lastly, Section 260.12 provides that marketers can make unqualified recyclable claims if the entire product or package, excluding minor incidental components, is recyclable. If any component significantly limits the ability to recycle an item, or if the shape, size, or some other attribute of the item makes it unacceptable to recycling programs, the product should not be marketed as recyclable.

Recycled Content

Section 260.13 states the basic rule that it is deceptive to misrepresent that a product or package is made of recycled content. It also provides that it is deceptive to represent that an item is made of recycled content unless it is composed of materials that have been recovered from the waste stream either during the manufacturing process (“pre-consumer”) or after consumer use (“post-consumer”).

Marketers can make unqualified claims of recycled content if the entire product or package, excluding minor incidental components, is made from recycled materials. Otherwise, the recycled content claim must be appropriately qualified.

Recyclability Has Become a Plastic Issue

In the United States, legal actions involving recyclability claims have ballooned over the past several years. Searches in August 2024 of the Columbia Law School’s U.S. Climate Change Litigation database and the NYU School of Law’s Plastics Litigation Tracker database identified 14 recent lawsuits that include allegations of deceptive recyclability claims.

All these lawsuits involve recyclability claims made about plastic products or plastic packaging; none involve recyclability claims relating to products or packaging composed of fiber-based materials.

This result should not be surprising. The recyclability of fiber-based product and packaging materials has been established for decades, and an overwhelming majority of U.S. consumers and communities have access to recycling programs that accept fiber-based materials.

A 2021 study by Resource Recycling Systems on behalf of the American Forest & Paper Association (AF&PA) found that 94% of the U.S. population and 84% of U.S. communities have access to paper and paperboard recycling programs (curbside and drop-off).

Given growing concerns about the negative environmental impacts of single-use plastic products and packaging, it’s likely the number of legal actions challenging plastic recyclability claims will continue to grow.

Revision of the Green Guides

The FTC is currently revising the Green Guides, although the agency hasn’t committed to a specific timetable for completing the revision.

The FTC also hasn’t indicated what specific changes it expects to make. However, when the agency initiated the revision process, it sought public comment on numerous substantive questions relating to the Guides, and those questions suggest several issues for FTC focus.

In response to the FTC’s request, the AF&PA submitted comments on a wide range of issues. Here are three important issues the AF&PA’s comments addressed.

Recyclability

The Green Guides provide that companies can make an unqualified “recyclable” claim when recycling facilities are available to at least 60% of consumers or communities where a product is sold. The FTC requested comments regarding whether the 60% threshold should be changed. AF&PA recommended maintaining the current 60% threshold.

The FTC also asked whether the Guides should include provisions relating to “recyclable” claims for products or packaging collected by recycling programs, but not actually recycled.

AF&PA argued that such provisions aren’t needed, writing that: “The Green Guides have been useful through today by focusing on an access rate...The system is proven and it works...AF&PA believes establishing a recycling rate mandate to document recyclability is unnecessary.”

Recycled Content

The FTC sought comments regarding whether claims should distinguish between pre-consumer and post-consumer recycled content. AF&PA recommended that the FTC not change the current description of “recycled content” in the Guides, writing that: “AF&PA believes that ‘pre-‘ and ‘post-consumer’ designation for recyclable materials is not a meaningful distinction in manufacturing or for consumers.”

Chemical Recycling/''Advanced Recycling''

The FTC also requested comments regarding any potentially deceptive environmental claims that are not currently covered in the Guides. AF&PA identified chemical recycling as an issue the Guides should specifically address.

Chemical recycling (sometimes called “advanced recycling”) refers to the conversion of post-use plastic materials into base chemicals that can be used to make either new plastic products or fuel for energy recovery.

AF&PA noted that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency differentiates “recycling” from “energy recovery” and recommended that the following language be added to the Guides:

EU Regulation of Environmental Claims

The regulation of environmental marketing claims in the European Union is poised to change in fundamental ways. Earlier this year, the EU adopted Directive (EU) 2024/825, which prohibits the use of certain types of environmental marketing claims, including, for example, generic claims such as “environmentally friendly” and “eco-friendly,” unless a company can demonstrate excellent environmental performance relative to the claim.

This Directive also contains rules relating to the use of claims based on greenhouse gas emissions offsets and the use of environmental or sustainability labels.

The EU is currently considering a directive known as the Green Claims Directive. If enacted as currently proposed, the Green Claims Directive would establish a new regulatory regime for specific (as opposed to generic) environmental marketing claims and for environmental labels and labeling schemes. It would require companies to perform a rigorous assessment to substantiate claims and have the assessment verified by a designated official before a claim can be used or published.

The Bottom Line

The potential benefits of making legitimate environmental claims in marketing materials and on product packaging are substantial. They can enhance a company’s reputation and may lead to higher sales.

However, business leaders must be careful when making environmental claims. Governmental authorities are placing such claims under greater scrutiny, and litigation risk is rising, primarily due to the actions of state attorneys general and environmental activists.

While it’s impossible to eliminate all risks associated with making environmental claims, there are three steps businesses operating in the U.S. can take to minimize those risks.

- Make sure your marketing, merchandising, and packaging design personnel are thoroughly familiar with the FTC’s Green Guides.

- Ensure that you are aware of any state laws and/or regulations that prohibit, or impose specific requirements on environmental claims.

- Ensure that you have credible and scientifically valid evidence to substantiate any claims you make.

To Learn More...

International Paper is one of the world’s leading producers of renewable, fiber-based packaging, and one of the largest recyclers of used cardboard. To learn more about International Paper’s approach to making fiber-based packaging a vital part of a circular economy, take a look at our white paper “Thinking Inside the Box: A Circular Approach to Extending the Lifecycle of Fiber-based Packaging.” And if you’d like to learn more about our commercial recycling services, visit International Paper’s website.

The regulatory landscape continues to evolve rapidly and somewhat unevenly across many states. We will continue to provide updates to our content as new legislation is passed and the regulatory frameworks are modified.

The Many Shades of Greenwashing

In 2007, TerraChoice Environmental Marketing conducted a study to examine the prevalence of greenwashing. The firm collected 1,753 environmental claims on 1,018 products and found that all but one of the products in the study exhibited greenwashing.

The researchers also identified six patterns in the misleading claims they encountered, and the firm described those patterns in a paper titled, “The Six Sins of Greenwashing.” In 2009, TerraChoice updated its research and added a seventh “sin” to the list.

The categories of greenwashing described by TerraChoice have been adopted and expanded by later commentators. Here are the seven “sins” of greenwashing identified by TerraChoice.

- The hidden trade-off claim—When a claim suggests that a product is beneficial for the environment based on only one or two attributes while ignoring other environmentally important attributes.

- A claim with no proof—When a company makes an environmental claim about a product but does not provide proof or point to accessible supporting information.

- Vague claims—Claims that are so broad or poorly defined that consumers are likely to misunderstand or misinterpret their meaning. Classic examples of this type of claim would include “eco-friendly” and “non-toxic.”

- Irrelevant claims—When a company makes an environmental claim that, while truthful, is not helpful for consumers who are seeking more environmentally sustainable products.

- Lesser of two evils—When a company makes a claim that may be true within a particular product category, but distracts the consumer from seeing the negative environmental impacts of the category as a whole.

- False claims—When a company makes an environmental claim that is simply false or untrue.

- Misleading labels—When a company uses images, words, or logos that imply a third party has endorsed an environmental attribute of its product, even though no such endorsement exists.

The behavioral opposite of greenwashing is called “greenhushing.” Rather than touting the environmental credentials of their organization or the environmental benefits of their products, companies that engage in greenhushing deliberately do not publicize their sustainability or other environmental commitments or accomplishments.

Most observers contend that companies practice greenshushing for two main reasons.

- They want to avoid becoming a target of the “anti-woke,” “anti-ESG” backlash that has recently gained traction in the U.S.

- They want to avoid accusations of greenwashing.

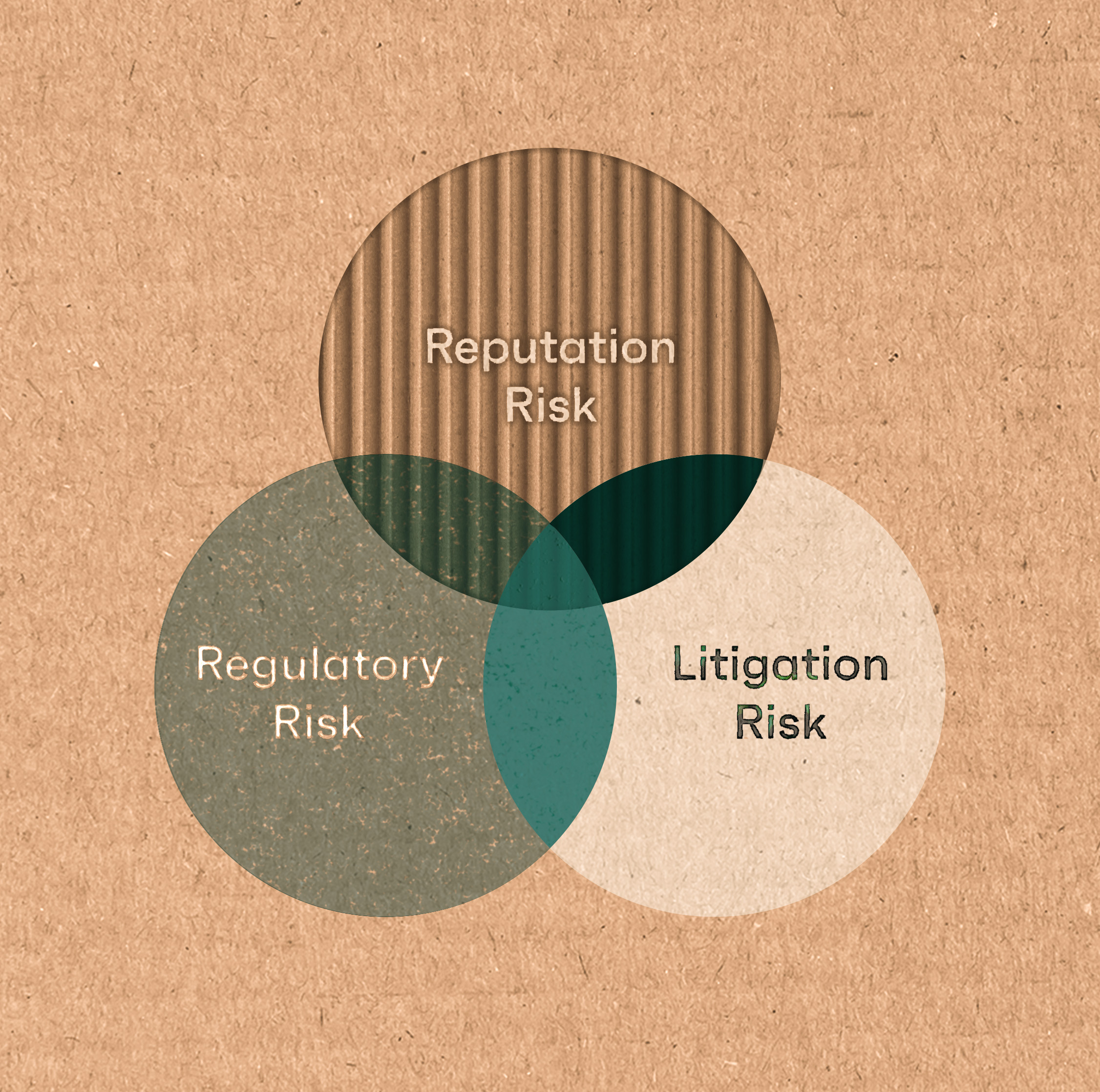

The Three Faces of Greenwashing Risks

Greenwashing can expose companies to three major types of risks, as the following diagram illustrates.

Reputation Risk

The greatest long-term risk of greenwashing is the loss of consumer trust, particularly among those consumers who make environmental concerns a major factor in their buying decisions.

In a 2020 survey of UK consumers by Shift Sustainability, survey participants were asked how they would react if they thought a company was not living up to its environmental/sustainability claims. Fourteen percent of the respondents said they would never buy the company’s products or services again, and another 48% said they would buy the company’s products or services “as little as possible.”

In addition, 40% of the survey respondents said they wouldn’t recommend the company to friends or family even if they liked the company’s products or services, and another 17% said they would tell their friends and family to stop buying from the company.

Regulatory Risk

Greenwashing can also trigger enforcement actions by regulatory authorities such as the FTC.

The FTC sued two large retailers for falsely marketing textile products as made of bamboo when the products were actually made of rayon derived from bamboo.

Both companies were also charged with making deceptive environmental claims by asserting that the “bamboo” products were produced using eco-friendly processes when the process of converting bamboo into rayon involves the use of toxic chemicals and results in hazardous emissions.

To settle these enforcement actions, the retailers agreed to pay substantial civil penalties and to make changes in their marketing practices.

Litigation Risk

Litigation risk is rapidly becoming the most notorious type of greenwashing risk. Litigation risk encompasses lawsuits brought by state attorneys general and by private plaintiffs, usually on the basis of state laws.

A recent case involving a manufacturer of single-serving coffee pods illustrates how significant litigation risk can be. In 2022, the manufacturer agreed to pay $10 million to settle a class action lawsuit that alleged the company deceptively marketed its pods as recyclable.

The pods were primarily made of polypropylene, which is accepted for recycling in more than half of U.S. recycling facilities. However, the small size of the pods meant that many recycling facilities were unable to process them, and in addition, the presence of coffee residue and metal contaminants in the used pods rendered them unsuitable for recycling.

The company’s packaging displayed the slogan “Have your cup and recycle it, too” and included detailed recycling instructions, including a “check locally” notice. However, the plaintiffs argued that the “check locally” qualifying language was not precise enough to avoid misleading consumers about the actual recyclability of the pods.